March 17, 2014

Ramiro Gomez's parents grew up poor in rural Mexico. His father dropped out of school after sixth grade to work. His mother made it through high school before leaving to help support her family. Living together in America, they took on the demanding jobs that many immigrants do: Truck driving, construction labor, janitorial work, housecleaning. Their biggest motivation to get through several jobs a day was their only son, Ramiro.

Ramiro had a creative streak even as a toddler growing up in the San Bernardino Valley. At times his mother would find he had stolen away her lipsticks to draw on scrap paper. Little did she know Ramiro would eventually take to real paints and real canvases, drawing as a way of life.

She also couldn't have imagined Ramiro's favorite thing to paint: People like herself and her husband.

"Being an artist and their child," says Gomez, "I can do something away from their labor, but at the same time speak to their importance in shaping me." He sees the story of laborers as the story of the American dream. It's one that he's part of, one that he feels a duty to depict on canvas.

Yet, there's a twist to his story of the stereotypical first-generation American, one that Gomez finds ironic. Although his parents raised him to value education and work hard so that he would never have to perform menial labor, Gomez found himself at age 20 working as a nanny to a rich family in West Hollywood.

At the time, Gomez's career wasn't looking so hot.

He had been accepted on scholarship to the prestigious Cal Arts, but the program wasn't a good fit. He struggled to produce work that he felt honest to himself, and he didn't enjoy being far from his family. So Gomez dropped out. Desperate to pay the rent, he took the first job he could find.

At the time, Gomez was ready to leave the art world entirely. But he couldn't help dabbling. Looking after the two toddlers in West Hollywood, he would sometimes have spare moments to flip through the magazines on the coffee table, things like Dwell and Architectural Digest.

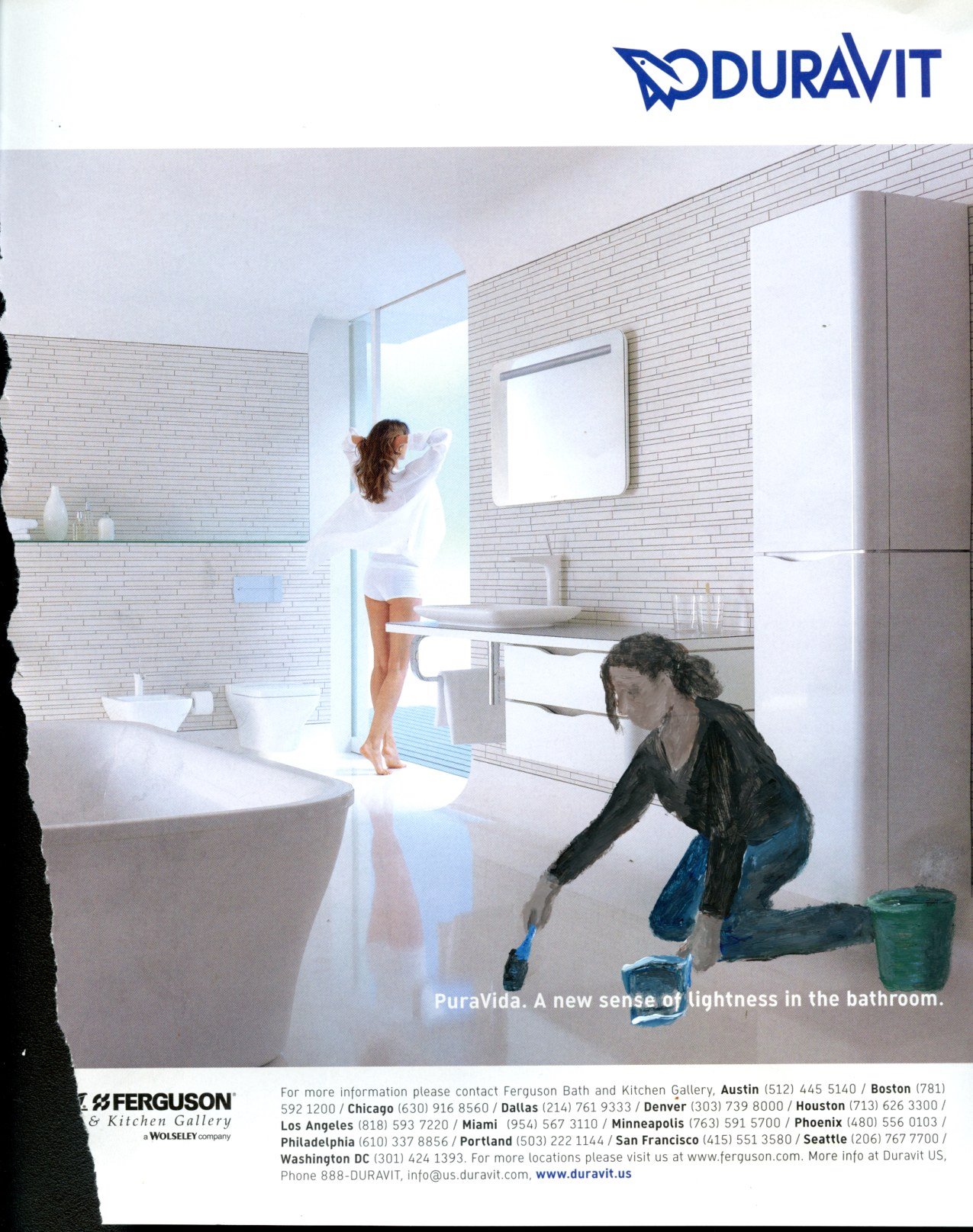

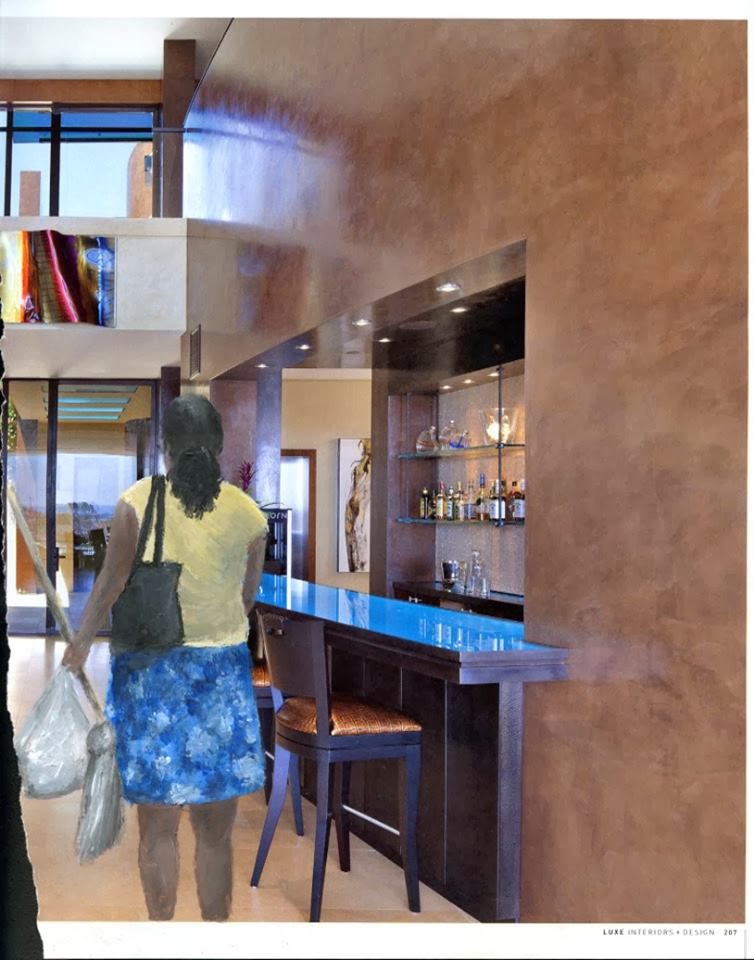

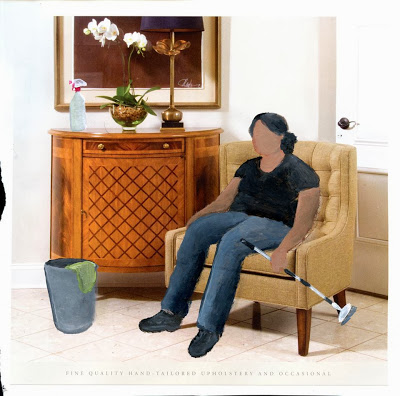

As he browsed through the photo spreads of lavishly decorated homes, his eyes gazed over moms, dads and kids lounging on couches or enjoying a fine meal. But where were the people like himself? Where were the workers?

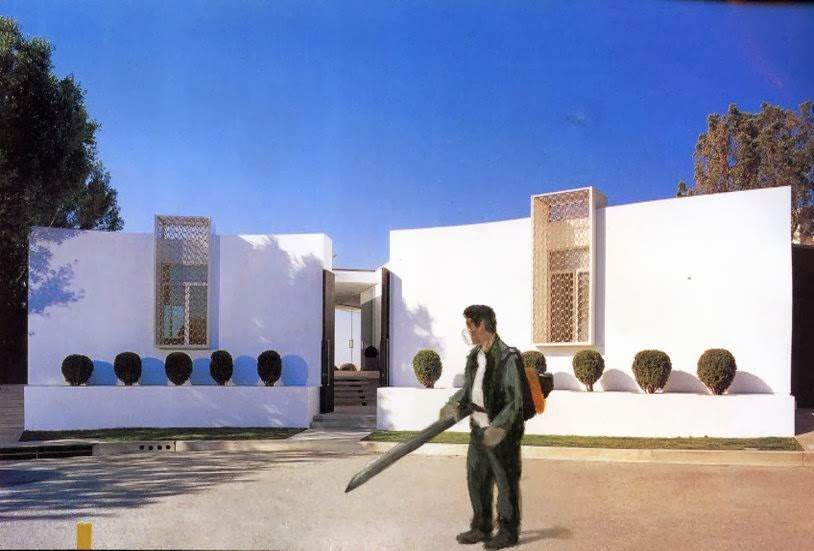

He began painting them into the scenes. Women with mops, standing in luxurious kitchen with pristine white tiles. Men with rakes and leaf-blowers, stationed at neatly trimmed hedges. All with Gomez's same dark hair, and his same copper skin tone. They were the women and men who could have been his mother and his father. Yet, none of them were depicted with facial expressions.

"Realism can only explain what your eye is seeing," says Gomez. "It doesn't explain what your heart feels." Instead of painting eyes and mouths, Gomez focuses on body language, creating figures with rounded shoulders and stooped backs, similar to the peasants in the paintings of one of his inspirations, the 19th-century painter Jean-Francois Millet.

The magazines felt like a way for Gomez to finally create art that, finally, felt true to his life and experiences. He just needed people to see it.

So Gomez decided to think outside of the box. Way outside... into the streets of West Hollywood, in front of homes like the one where he worked. Instead of creating figures on magazines, he would create figures out of cardboard, their size nearly true to life.

The first time Gomez placed a cardboard cutout, he was scared, he recalls. The cutout was painted to resemble a gardener, wearing thick green pants and wielding clippers.

"As I'm going out there, I'm at risk at being confronted," says Gomez, thinking back on the early days.

"With art, it's so subjective, you don't know what the reactions are going to be," he says. "The reactions were something I couldn't control."

The owner smiled and told Gomez he thought it was great. Then he waved over his gardener. The gardener stared for a moment. Then he went straight back to work, without uttering a word.

Gomez returned to his West Hollywood apartment and thought, "Am I ready for this?"

In the end, he decided to go for it - to pursue this crazy project far from L.A.'s art galleries and museums, that wasn't earning him any money, but in fact, helping him to lose it. His began to see his mission as a way to bring art to the public in surprising ways.

Eventually, the cutouts attracted the eyes of more than homeowners and gardeners; activists, journalists and art connoisseurs all took notice of this unusual project.

These days, now that he has quit his nanny job to pursue art full time and has sold roughly 50 works, Gomez has a measured approach to fame and success.

"The reason I got here was I just thought of my own feelings and my own thoughts, and other people connected," he says. "All I can do is just naturally grow."

If the attention has made Gomez confident, it has also made him ambitious.

His goal is to be a professional artist with works in museums around the world, and to eventually experiment with a variety of media, such as video, photography, and sculpture.

"I want to be painting in my 80s, just as my inspiration, Hockney," says Gomez.

In February, Gomez began renting a space at Keystone Art Space in Glassell Park, among more than a dozen other artists.

On a recent evening, Gomez is getting ready to prep a five-foot-wide canvas for a work in his Hockney series. So far, a few strips of bright green appear at the edges, hemmed in by blue painters tape. About half a dozen rolls of extra tape lie on the ground.

He apologizes that there is only one folding chair to share between two people; the space is still new, but he plans to bring a couch, and maybe a projector screen to watch films. Overhead, a string of white lanterns bobs beneath the soaring ceiling, offering bright illumination.

Gomez keeps examples of past works close, reminders of the people he wishes to depict.

Two framed photographs, both of cutouts placed in West Hollywood, lean against the wall. They were taken by Gomez's partner of 8 years, a film editor. On his desk, fashioned out of a grey folding table, Gomez keeps drawings of cleaning products done on industrial cardboard--a bottle of Lysol, a mop, Windex.

Gomez sits down, and stirs his paints in a plastic tray with a narrow brush. He whips out his iPhone, and selects a photo of a janitor at LAX pushing a trash bin. He begins to paint the same figure over a photograph of a Jeff Koons sculpture standing in a white-walled museum.

Without making a single sketch, Gomez puts brush to paper. Gradually, the outline of a man appears, shoulders rounded over.

This is part of his new series, which places janitors and security guards and other Latino workers in museum settings - not just within wealthy homes.

Gomez doesn't feel the fear he once had about viewer reactions.

"I'm trying to get you to sympathize, connect, understand, question, think, wonder--just engage you," he says.

And by the same token, he says he doesn't pin any hopes on being able to cause social change. He only hopes to show, in a gripping way, his own point of view - his own life story.

"I'm just an artist primed to talk about a certain thing," Gomez says. "By no means am I solving anything."

Browse the photos below for a sampling of Gomez's work. Click the thumbnails to enlarge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

View more of Gomez's paintings on his blog and Facebook pages.